Have you ever wondered how calorie intake is actually calculated? We run through the basics here, as well as sharing some helpful advice on building good habits at meal times.

What is a calorie?

The precise scientific term kilocalorie (or kcal) is technically defined as the amount of energy needed to increase the temperature of one litre of water by 1°C, at sea level. This is the familiar figure displayed on the nutritional information of packaged foods, and is used to calculate energy intake. While one kilocalorie is actually equal to 1,000 calories in scientific terms, the word ‘calorie’ is more usually used to refer to kilocalories when we talk about nutrition. To avoid confusion, this article will use the term ‘calories’ throughout when referring to kcals.

So how many calories do we actually need?

The honest answer to this question — although admittedly not the most satisfying — is that it depends on the person. Not everyone has the same energy requirements, as these will vary depending on an individual’s age, gender, weight, height, activity level and health status (Osilla, Safadi & Sharma, 2021). Caloric needs are calculated based on your total energy expenditure (TEE) which refers to the amount of calories/energy burned on a given day. TEE is made up of a combination of resting energy expenditure, activity energy expenditure and the thermic effect of food. The majority of calories burned in a day are from your resting energy expenditure (REE) and used in homeostasis, or the maintenance of essential bodily functions such as breathing, blood circulation, thermoregulation, moving components in and out of cells and other physiological processes.

Activity energy expenditure (AEE) refers to how much activity you do in a day and at what intensity level, e.g. whether you’re going to the gym or walking every day, or living a more sedentary lifestyle. The final component in making up our energy expenditure refers to the thermic effect of food (TEF). This is the energy your body uses to digest and absorb the food you have consumed (Hall et al., 2012). Some foods require more energy to digest than others, and we’ll touch on this later in the article.

Taking all of this information into consideration, government guidelines in Ireland suggest that the average woman requires approximately 1,800-2,000 kcals a day depending on activity level, with more sedentary people fitting into the lower end of this bracket and more active individuals at the higher end. The same concept applies to men, but the suggested range for them lies between 2,000 and 2,500 kcals a day (FSAI, 2011). It is important to understand that these figures are not set in stone, but are merely averages to use as general guidelines. Someone like an intercounty athlete may require far more calories than what is recommended above, while an individual who does not exercise, has a very sedentary job or has some form of a disability may require less.

There are many energy equations available to calculate a more individual caloric requirement, such as Mifflin St. Joer (1990), which has been shown to be a reliable predictive equation (Frankenfield, Roth-Yousey & Compher, 2005). Equations like this take into account body weight, height, age and gender to calculate your RMR. Additional activity energy requirements can then be added on via physical activity levels (PAL); this can be easily accessed in the Nutritics app. If you are unsure of your current activity status, it always helps to keep an activity journal for a week and record your normal routine.

Where do these calories come from? The bulk of these calories come from the three main macronutrients: carbohydrates, proteins and fats. One gram of carbohydrate or protein contains four kcals, while one gram of fat has nine. Once you know how many of these macronutrients are in any given food, you can calculate how many calories — or how much energy — that food contains. For example, a 40g chocolate bar has 215 kcals. These are made up of: 22.9g of carbohydrates (22.9 x 4 = 91.6 kcals) 2.9g of protein (2.9 x 4 = 11.6 kcals) 12.4g of fat (12.4 x 9 = 111.6 kcals) Total calories (91.6 + 11.6 + 111.6 = 214.8 kcals), which rounds to 215 kcals.

Knowing which macronutrients make up your food can potentially lead to better food choices.

Why do I need to know how many calories I need? Knowing how many calories you need in a day allows you to maintain a healthy weight and to support bodily functions, balancing the number of calories you consume through food and drink with those burned through physical activity. Think of a carefully-balanced see-saw: if the see-saw leans one way, you lose weight, and if it tips the other, you gain weight. Your maintenance levels are also useful when choosing to lose or gain weight; eating 300-500 kcal above or below your maintenance level is recommended to achieve the desired weight goal (Raynor & Champagne, 2016 & Iraki et al., 2019).

5 tips for building good habits at meal times

1. Know your food choices. Being aware of what is in food is very important in controlling your calorie intake. Foods containing high amounts of fat can lead to a high calorie count — something as small as one teaspoon of peanut butter has 85 kcals — so it may be wise to portion them out tactically or opt for low-fat dairy products and leaner meats. You should also be mindful of portion sizes when it comes to sauces, as they may contain fat and sugar. When consumed in liquid form, it’s easy for calories to go unnoticed. Drinking still/sparkling water instead of sugary fizzy drinks or other calorie-dense beverages will save a lot of extra calories at meal time. It’s also important to remember that alcohol contains calories too; in fact, every gram of alcohol contains 7 kcals, more than either carbohydrates or proteins, so be aware of how much you drink with your meal.

Nutritics’ recipe function has a built in traffic light system to provide detailed information of the nutritional profile of a dish. Click the light bulb icon beside a nutrient to see suggestions provided for ways to reduce the amount of this nutrient in your recipe, e.g. as seen with fat in the image below.

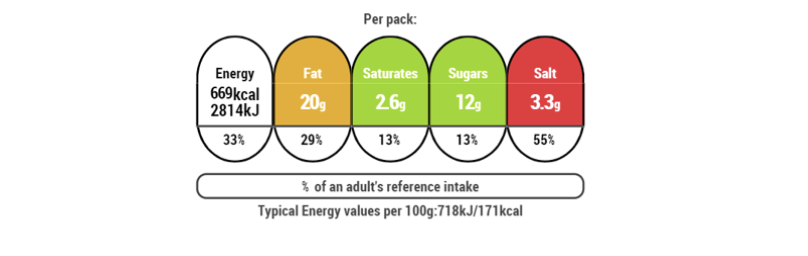

2. Know your labels. Being able to read labels can also help you make smart food choices, based on their calorie content and nutritional profiles. A useful way of monitoring this is the ‘traffic light’ colour coding system.

- Green means this food is a healthy choice, likely to be low in fat, salt and sugar. If you buy a food that has all or mostly green on the label, you know straight away that it's a healthier choice.

- Amber indicates neither high nor low levels, so you can eat foods with all or mostly ambers on the label most of the time.

- Red on the label means the food is high in fat, salt and/or sugars. These are the foods that should be cut down on and monitored.

The labels on packaged foods can also provide you with helpful information around ingredients, macronutrient breakdown and fibre content, and can even suggest a suitable serving size per person to avoid consuming too many calories.

3. Consider your cooking methods. Choose to grill, steam and boil foods instead of frying them — oil contains a lot of fat and hence a lot of calories. If cooking with oil, try not to add more than one teaspoon per serving and use nonstick cookware. Not only does this eliminate the need for lots of oil, but it’s easier to clean, too.

4. Focus on satiety. Include more whole grains at meal time to regulate appetite. The fibre content in these complex carbohydrates means they take longer to be digested and will keep you full for longer (Barber et al., 2020). This can also be said for protein, the most satiating macronutrient — meaning it takes the most amount of energy to metabolise fully, and helps you feel satisfied for longer after eating (Leidy et al., 2015).

5. Know how to build a calorie-friendly meal. When building a calorie-friendly meal, National Healthy Eating Guidelines are designed to help you. Not only do they help guide your portion sizes, but it also acts as a checklist, reminding you to include those all-important vegetables and whole grains. Different countries provide different guidelines and visual representations, e.g. Ireland uses the Food Pyramid and the UK uses the EatWell Guide.

References

- Osilla, E. V., Safadi, A. O., & Sharma, S. (2021). Calories. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Raynor, H. A., & Champagne, C. M. (2016). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Interventions for the Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(1), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.031

- Iraki, J., Fitschen, P., Espinar, S., & Helms, E. (2019). Nutrition Recommendations for Bodybuilders in the Off-Season: A Narrative Review. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 7(7), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7070154

- Hall, K. D., Heymsfield, S. B., Kemnitz, J. W., Klein, S., Schoeller, D. A., & Speakman, J. R. (2012). Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 95(4), 989–994. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.036350

- Frankenfield, D., Roth-Yousey, L., & Compher, C. (2005). Comparison of predictive equations for resting metabolic rate in healthy nonobese and obese adults: a systematic review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105(5), 775–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.005

- Food Safety Authority of Ireland. (2011). Scientific recommendations for healthy eating guidelines in Ireland. Food Safety Authority of Ireland

- U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/

- Leidy, H. J., Clifton, P. M., Astrup, A., Wycherley, T. P., Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S., Luscombe-Marsh, N. D., Woods, S. C., & Mattes, R. D. (2015). The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 101(6), 1320S–1329S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.084038

- Barber, T. M., Kabisch, S., Pfeiffer, A., & Weickert, M. O. (2020). The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre. Nutrients, 12(10), 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103209